He walked into my clinic and placed a bottle on my table. A bottle of insecticide. Trigeminal neuralgia has long been called the ‘suicide disease’. In recent times, it briefly returned to public conversation when actor Salman Khan spoke about his experience with facial pain. But two decades ago, one man gave me a lesson in its brutality that I will never forget.

Until 2004, I performed Microvascular Decompression (MVD) surgery for trigeminal neuralgia, but not with the urgency and singular focus that now defines my practice. Then came an afternoon that changed the course of my life and shaped the work we do at our neurosurgical centre in Pune today.

My clinic hours were over and I was ready to leave when my secretary hesitated at the door. “There’s a gentleman who has come from very far,” she whispered. “He… looks quite distressed. I think you should see him.” I asked her to send him in. Years of treating trigeminal neuralgia had prepared me for patients in pain, yet this man’s appearance was startling. He was unshaven for days. His eyes were heavy, his gait unsteady, and his face contorted with constant agony. His right hand clutched a frayed bag as if it contained his last hope.

“Are you Dr Jayadev?” the patient who was in his late forties or perhaps early fifties asked, teeth clenched. Then, he sat down slowly, reached into the bag and placed a bottle on my desk. “Insecticide,” he grimaced. “Please tell me you can cure this pain. Otherwise, I will drink this and end it.”

It felt like a scene from a film, except it was painfully real. He had been suffering for six long years. The slightest movement — speaking, chewing, shaving, even a breeze on his face — triggered electric stabbing pain. He was surviving on high doses of anti-seizure medications — Carbamazepine and Gabapentin. Yet, there was no relief from the relentless torment.

I knew the stock phrases associated with this disease — “the worst pain known to mankind”, “pain you wouldn’t wish on an enemy”. I had always believed those belonged to another time when treatment wasn’t available. But here he sat, living proof that the disease could still drive a person to the edge, even in the modern era of neurosurgery .

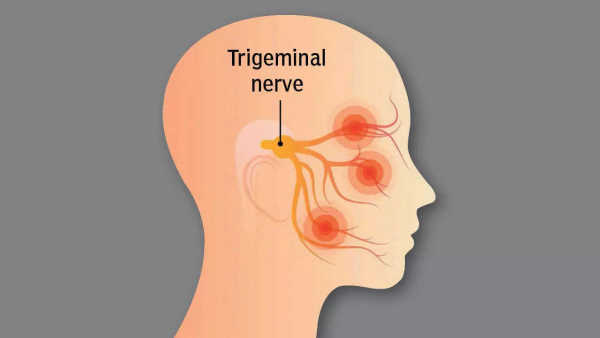

Like other patients of trigeminal neuralgia, he had been to various dentists in vain. The day he came to me, he was a bit drunk — a common coping mechanism to numb the pain. He did not need convincing. Neither did I. He needed surgery. Urgently. We operated the very next morning. Under the microscope, we found the culprit — a small artery that had dug into the trigeminal nerve at the point where it enters the brain, striking it with every heartbeat like a tiny hammer.

The trigeminal nerve is the main nerve that carries sensation from the face to the brain, letting you feel your cheeks, jaw, lips, and eyes. We gently freed the artery and placed Teflon between it and the nerve. His pain disappeared immediately after surgery.

To me, this outcome was expected. To him, it was a miracle. For the next two days, he was, quite literally, mad with joy — laughing, crying, celebrating every pain-free sip of water and every word

uttered without effort. Before being discharged, he held my hand and pleaded: “Tell people. Tell them this can be cured. No one should suffer like this.”

That encounter moved me. It made me realise that awareness was as important as skill. Patients needed to know there was hope. And surgeons needed to treat this with the precision and dedication it deserved. I was young and charged up. So, I opened a microvascular surgery centre in Pune. Over the past 21 years, my team and I have performed over 2,700 MVD surgeries, 1,800 of them for trigeminal Neuralgia. We have seen patients who once rubbed red chilli paste on their face, tried alcohol, used nerve-cutting procedures, radiofrequency burns, injections, gamma knife radiation — you name it. But these were all temporary measures aimed at destroying the nerve, not the cause.

Dr Peter Jannetta, the pioneer of MVD, showed the world that treating the root problem — the blood vessel compressing the nerve — offers the best chance of cure. Our experience only reinforces this truth. Done early, by a focused, experienced team, MVD gives patients their lives back. Proof of this is the patient testimonies I keep on a hard disk in my office.

That afternoon, the insecticide bottle on my desk was more than a cry for help. It was a reminder of our responsibility as doctors. Today, when patients walk in, I tell them there’s hope. And as long as we stand guard, nobody should ever feel driven to pick up the bottle again.

Dr Jayadev Panchawagh, Consultant Neurosurgeon , Sahyadri Super Speciality Hospital, Deccan Gymkhana, Pune

He spoke to Sharmila Ganesan Ram

Contact to : xlf550402@gmail.com

Copyright © boyuanhulian 2020 - 2023. All Right Reserved.